Louisa May Alcott. Her name conjures images of sisters giggling, a house full of love, running through fields with a hiked up petticoat. But you’re likely imagining the Marches, the family at the center of her most famous novel Little Women written in 1868. Or the 1994 film version. Or the 2019 film version. As cherished as this semi-autobiographical story has become, Little Women isn’t Louisa Alcott’s true story. There’s so much more than meets the eye. The woman behind one of the most beloved stories in American literature had a complicated, unconventional, and fascinating life. From childhood through adulthood, Louisa Alcott bucked expectations put upon nineteenth century women in America. Her upbringing, ideals, and experiences came together to form an author unlike any other of her time, or since.

Family is everything

Louisa Alcott was born on November 29, 1832 in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Her family consisted of father Bronson Alcott, mother Abigail May, and sisters Anna, Elizabeth, and Abby May. Louisa’s world view, life path, and career were all directly influenced by her family. She herself said “painful as it may be, a significant emotional event can be the catalyst for choosing a direction that serves us — and those around us — more effectively.” To understand Louisa’s life and writing, you have to learn about her family and the significant events they shared.

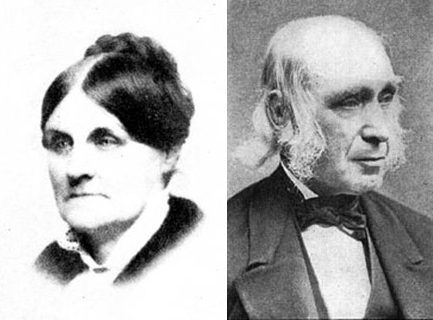

Meet the parents

Abigail and Bronson raised their four daughters on self-reliance, compassion, and self-expression. Louisa in particular embodied all these qualities throughout her life. Louisa’s mother, Abigail, was passionate, wise, and generous. Her involvement in causes like abolition, women’s rights, and temperance laid a blueprint for work Louisa would do later in her own life. Abigail’s catchphrase “hope, and keep busy” made a lasting effect on Louisa — in Little Women, Marmee even says it to her daughters. And on the opposite end of the parental spectrum: say hello to Bronson Alcott! Bronson loved his family, but was an eccentric man. He was at the epicenter of the New England Transcendentalist movement, a group who believed that every individual has intuition and knowledge that transcends logic or the senses. The transcendentalists challenged society’s conformity and took progressive stances on issues such as prison reform, poverty, and slavery. Bronson’s beliefs and dedication to the movement were top priority to him. He was a vegetarian, abolitionist, education reformer, and women’s rights advocate. His commitment to his ideals, while admirable, also put the family in dire circumstances more than a few times.  Source: uudb.org

Source: uudb.org

The Alcott sisters

The Alcott sisters’ characterizations and relationships have some of the strongest parallels between the characters in Little Women and Louisa’s real life. Similar to the March daughters in the book, the Alcott girls loved and revered their mother. As children, she and older sister Anna would put on plays and act together like Jo and Meg in the book. What doesn’t happen in the novel? In 1858 in Concord, she and Anna formed the Concord Dramatic Union which is still running today! Perhaps most famously, the character Beth parallels Louisa’s sister Lizzie. (Spoilers ahead!) Both Beth and Lizzie passed at a young age and are remembered as sweet dear girls. But Lizzie wasn’t so docile, especially at her life’s end. She had angry outbursts and was diagnosed with hysteria before passing away due to scarlet fever. The way Louisa writes Beth in Little Women preserved the gentle, rosy version of Lizzie held beloved by her sister. While she never married or had any biological children, Louisa’s family grew through her sisters. In 1879, she adopted her niece (called Lulu, but also named Louisa May) when her sister May passed away in Lulu’s infancy. Louisa was Lulu’s caregiver until the end of Louisa’s life in 1888. Louisa’s sense of familial duty also held strong when she stepped in to support sister Anna. Anna’s husband passed away in 1870, leaving her with two sons to care for. To ensure Louisa’s inheritance would go to Anna’s family when she was gone, Louisa adopted Anna’s son John.

‘Til death do us part

The end of Louisa’s life was spent in Boston, caring for her mother who passed away in 1877. In 1888, she also cared for her ill father until his passing. Two days after he died, Louisa Alcott passed away at age 55. The cause of death has been speculated to be related to stroke, lupus, or mercury poisoning from treatment she received for typhoid pneumonia during the Civil War. Louisa May Alcott is buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord on “Author’s Ridge,” an honor for the writer who passed too soon.  Source: U.S. National Park Service

Source: U.S. National Park Service

The realities of Alcott’s life and how they affected her writing

Fans of Little Women get a taste of real people and events inspired by Louisa Alcott’s life, but there’s so much more to understand about the complexities of this prolific American writer.

Education, journaling, and the right kind of influences

Louisa’s father, an education reformer, believed that children should enjoy learning and have a sense of self in their learning. In fact, we have Louisa May Alcott’s father to thank for inventing recess and many modern educational practices. As her main teacher, Bronson’s teaching style and ideals translated to Louisa. She was reading and writing from an early age, developing her own perspectives and observations. Louisa also kept journals, documenting everything from her passions to events to the challenges of controlling her temper. This habit would continue throughout her life and have given scholars and historians primary accounts to explore and learn more about the real Louisa Alcott. In addition to her father, Louisa learned from her neighbors and philosophers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson (whom she allegedly had crushes on!). They admired Bronson as fellow Transcendentalists and were close friends of the family.

Alcott’s feminist perspective was never a secret. She didn’t subscribe to the binding social norms placed upon women, and was supported by the free thinking her family modeled. One of her most staunch feminist stances? The injustice that women had to rely on a man or husband for financial security. The extreme poverty she experienced due to her father’s inability to provide financially shaped her world view and work (more on that later) Alcott also enlisted as a nurse during the Civil War as soon as she was eligible, in 1862. She believed in equality amongst the races as a daughter of abolitionists. The Alcotts lived along the Underground Railroad and even housed fugitive enslaved people in the mid 1800s. During the Civil war, she also continued her lifelong love of running — another non gender-conforming activity of the time. Her stint serving as a nurse was cut short after two months after contracting typhoid fever due to unsanitary conditions. She was sent home, but her time serving in the war only bolstered her ardent support of important social causes. Come the mid-1870s, her reforming work pivoted to women’s suffrage and temperance. She herself said “I like to help women help themselves…Whatever we can do and do well we have a right to, and I don’t think anyone will deny us.” With this fervent confidence, Louisa became the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts. This was a critical step in equality for women in her area and in the trajectory of suffrage in the United States. Alcott wove her activist ideologies into all her work, but it can especially be seen in novels like Work: A Story of Experience, written in 1873. This semi-autobiographical tale follows a woman’s search for meaning in life, and has Louisa’s views on feminism, women working, and independence woven throughout.

Poverty and ambition

Bronson’s imaginative professional ventures and commitment to ideals brought numerous challenges to the Alcott family. Despite his brilliant mind, he struggled to earn a living and often worked as a handyman or accepted financial help from others (including a down payment on the iconic Orchard House from Ralph Waldo Emerson). The welfare of the family became a lifelong concern for Louisa and a huge motivator in her career. She realized at a young age her father couldn’t provide for her mother and four daughters because of his impracticalities and ideals. In 1834, Bronson, Elizabeth Peabody, and Margaret Fulle opened the Temple School in Boston. It was a progressive school with an open learning space and conversation-based teaching style. So progressive, in fact, that Bronson enrolled a young Black girl in his school over 100 years before school desegregation in America. Upon hearing this controversial news, parents withdrew their children and the school closed by 1840.  Source: Louisa May Alcott is My Passion

Source: Louisa May Alcott is My Passion  Source: The Trustees of Reservations 1843 saw Bronson’s ill-fated creation of the Fruitlands, a utopian agricultural living community. This seven month experiment drove the Alcott family to destitution, her father was nearly suicidal, and her parents’ marriage on the rocks. At this point, Louisa vowed to make her family rich, and had ambitions of fame for herself. To fulfill her promise, Louisa contributed financial support in any way women could at the time. She said “I will make a battering-ram of my head and make my way through this rough and tumble world.” And batter through she did. She took on roles as a teacher, seamstress, governess, and even a servant for a brief period at an early age to financially contribute to the family. Eventually, Louisa turned to writing as a way to become financially solvent. Even before the success of Little Women, she earned money through writing. She wrote in different styles and learned how to tailor her work to specific markets, making her a more profitable, skilled, and confident writer. The remainder of her life and writing career was intensely fueled by keeping her family out of poverty, no matter the passion for the project.

Source: The Trustees of Reservations 1843 saw Bronson’s ill-fated creation of the Fruitlands, a utopian agricultural living community. This seven month experiment drove the Alcott family to destitution, her father was nearly suicidal, and her parents’ marriage on the rocks. At this point, Louisa vowed to make her family rich, and had ambitions of fame for herself. To fulfill her promise, Louisa contributed financial support in any way women could at the time. She said “I will make a battering-ram of my head and make my way through this rough and tumble world.” And batter through she did. She took on roles as a teacher, seamstress, governess, and even a servant for a brief period at an early age to financially contribute to the family. Eventually, Louisa turned to writing as a way to become financially solvent. Even before the success of Little Women, she earned money through writing. She wrote in different styles and learned how to tailor her work to specific markets, making her a more profitable, skilled, and confident writer. The remainder of her life and writing career was intensely fueled by keeping her family out of poverty, no matter the passion for the project.

From nom de plume to household name

In the late 1840s, publisher James T. Fields rejected her work and advised her, “Stick to your teaching, Miss Alcott. You can’t write.” She certainly proved him wrong. Alcott’s fame is attributed to Little Women’s success, but none of it would have been possible without the foundation of her family and the experiences she went through. They all impacted her writing, drive, and career choices.

Before we knew the March family

Alcott’s first published pieces were under the name A.M. Bernard. She wrote “potboilers” — stories that appealed to the public — as a reliable way to make money. Often they were racier or thrillers with storylines including drug use, murder, and forbidden love. As A.M. Bernard, Alcott was free to write without the limitations of being a female in the late nineteenth century. Her stories featured women characters who were strong, self-reliant, and imaginative. It was an early introduction to the female anti-hero in American literature. Her other pseudonym, Flora Fairfield, brought her the publication of her first poem, “Sunlight,” in 1852. It was followed by Alcott’s first published book in 1854 called Flower Fables, featuring stories for Ralph Waldo Emerson’s daughter. Louisa May Alcott’s first real taste of fame with her name on the cover was Hospital Sketches. Inspired from letters written home while she was a nurse in the Civil War, the book gave firsthand insight into being a woman in wartime. She also tackled racial prejudice, soldier’s stories, and hospital conditions all from her firsthand perspective.  Source: Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House

Source: Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House  Source: Applewood Books After the success of Hospital Sketches, her stories were published in The Atlantic, with works appealing to adults and children. Alcott was a successful writer, making money as an unmarried woman to help support her family. But her legacy was still unfolding.

Source: Applewood Books After the success of Hospital Sketches, her stories were published in The Atlantic, with works appealing to adults and children. Alcott was a successful writer, making money as an unmarried woman to help support her family. But her legacy was still unfolding.

Say hello to the Little Women

When the opportunity to write Little Women came around, it felt like a burden to Alcott. She was busy writing successful pieces as A.M. Bernard when her publisher told her he wanted something for younger girls. Alcott wasn’t interested, but he said the only way he would publish her father’s book was if she wrote this one. In yet another move to support her family, she took on the project. In her journal, Alcott noted “I don’t enjoy this sort of thing. Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters; but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.” In 1868 after ten weeks of writing at the desk her father built her at Orchard House, Little Women reluctantly came to be. Alcott and her publisher agreed it didn’t seem like it’d be a success, but the publisher’s daughter had a love of the story and it went to print. Initially published as a series of short stories, it eventually evolved into a book with a dedicated following. Both adults and children connected with the genuine characterizations and love found in the March family. Harriet Reisner, a twenty-first century biographer of Alcott’s life, highlights the preciousness that Little Women gave readers: The novel helped Alcott fulfill her childhood goal of keeping her family out of poverty. In 1869 Alcott was able to write in her journal: “Paid up all the debts…thank the Lord!” Though Louisa considered books like this “moral pap,” they were lucrative and led to two sequels: Little Men in 1871 and Jo’s Boys in 1886. Jo, the mirror of Louisa in Little Women, is the protagonist of the stories. Since the initial printing of 2,000 books were sold almost immediately in 1868, Little Women has never been out of print since. By the 1960s, the book had been translated into at least fifty languages and it was ranked among Time’s top 100 young adult books of all time in 2016.

The burden of fame

True to her promise, Alcott continued to write material that would sell to support her family — this meant children’s works were bountiful, and the saucier material took a backseat. She was now known as Louisa May Alcott, the architect of the beloved story of the March family. So, she stuck with the mentality of writing “anything to suit the customers,” despite her preference for a more intense style and darker themes. Louisa herself wrote, “Twenty years ago, I resolved to make the family independent if I could. At forty that is done. Debts all paid, even the outlawed ones, and we have enough to be comfortable. It has cost me my health, perhaps; but as I still live, there is more for me to do, I suppose.” Her career continued with stories based on her experiences and poetry that appealed to a wide audience. During her lifetime, she wrote over 300 pieces and changed the shape of American literature. We have Alcott to thank for creating multidimensional and relatable characters in novels, starring educated and strong heroines. In fact, Jo March is considered the first American juvenile heroine. For the first time, readers met with a young free-thinking woman who reveled in her individuality and flaws. Louisa May Alcott’s legacy elevates the empowerment of women and girls around the world and the embrace of individuality in literature and off the page.

Advice from Louisa

Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women has inspired readers for over 150 years, but it’s only a small portion of the woman who changed the landscape of American literature. Alcott’s career and literary works are intertwined with her lived experiences. And while you can’t emulate her writing through living her upbringing and tribulations, you can take some cues from the habits that carried her through. Grab a journal. All writing is practice, including informal journaling. Recount your day, work through challenging thoughts, delight in life’s joys. Whatever you write about, your skills will benefit from the practice as Alcott’s did. De-romanticize writing. Writing is often put on a pedestal of a divine calling, the words flowing through the author, the story needing to be told — but Louisa didn’t subscribe to this mentality. In an 1878 letter, she wrote “though I do not enjoy writing ‘moral tales’ for the young, I do it because it pays well.” Her practicality here is strangely inspiring. It’s ok to take a job writing unromanticized content — your livelihood can be built on a mix of passion and practical projects. “Hope, and keep busy.” In the same 1878 letter, Alcott shared “There is no easy road to successful authorship; it has to be earned by long and patient labor, many disappointments, uncertainties and trials.” Take Abigail May’s advice to hope and keep busy. Keep the faith that you’ll be successful and until then continue writing through challenges or rejections. Perhaps the best advice we can take from Louisa May Alcott is to be unabashedly ourselves in our work. Inject your perspective into your story development and characters. Your unique voice and point of view make your writing yours and yours alone. After all, there’s only one you.

Based in the suburbs of Chicago, Abby is a freelance copywriter focused on topics in education, women’s issues and accessibility, and social media. Abby’s life in writing started at age eight after learning her super cool camp counselor kept a journal. So she started a journal too! When not writing, Abby works with community members of all ages and abilities, creating opportunities for them to make theatre, explore their curiosities, and express themselves creatively (she’s also probably binge watching Gilmore Girls for the 500th time).